The Brown-Headed Cowbird Requiem

My Uncle Marty, my dad’s only sibling, passed away this week surrounded by family in his home up in Wisconsin’s Northwoods. Ron and I went back a few weeks ago to see him knowing the end was near. Marty was the keeper of our family stories. He had a knack of filling in the missing pieces with the best versions of our ancestors and of ourselves. This meant that sometimes the facts were altered like the broad strokes of a paintbrush hiding the dark colors with something brighter and better for all of us.

Unable to make the funeral, I yearned to be connected, so I picked up where Uncle Marty had left off. One of the last stories he shared was about our family’s history with Abbott Pennings, the founder of Saint Norbert College in DePere, Wisconsin. In Marty’s story, Abbott Pennings was a dear friend of my great-great- grandparents, Louis and Pheilomen (François) Colburn. Sometime in the late 1940’s when Louis was an old man, he donated his house and land to the college. The house was turned into a primate lab. Years later it was torn down, and no one seems to remember exactly where it once stood. Over the years I have collected other snippets of information. We were the distant relatives to Enos Colburn who has a park named after him in Green Bay. My great-grandfather Bearl Colburn was an inventor. My cousin Chad is the spitting image of our fifth great-grandfather, Jean-François d’Amours, Sieur de Courberon born in Kamouraska, Quebec in 1791. Past that I didn’t have a lot of information about my Colburn relatives. I grew up immersed in my mother’s big, fun-loving Irish Catholic clan. The Colburns by comparison were quiet, polite people consisting of my Uncle Marty and Aunt Linda and their two kids, my cousins, Tracy and Chad. My grandparents Bud (Heath) and Evelyn Colburn are long gone. Bud had a brother, Lee, and a couple of kids, but I only met them a handful of times. My grandma Evelyn was an only child. I remember her mom, my grandma Mamie, but she died when I was young. There were also two sisters, Verna and Glad, Bud’s aunts, who lived together in Milwaukee in a tiny house on 91st Street with a calico cat named Cookie. I loved all these people dearly, but with the exception of an occasional visit, they required little of me. I didn’t feel the sticky, messy glue of family when I was among them. Marty with his stories, colorful language, and sometimes raucous behavior made him the unlikely super hero that held us all together. In recent years, with the addition of nieces and nephews, and Marty’s frequent calls, I am grateful to the rekindled relationships I have with that side of the family, and with my sisters and their children.

Within an hour of researching my ancestors online, I traced them back to the early 1500’s, Paris, France. My great-great-great grandparents, Theodore and Célina (Desmarais) D’Amours de Courberon, came to the United States from Quebec to Redford, New York in 1852 (where our family name was changed to Colburn) before they made their permanent home in DePere shortly thereafter. They had twelve children. I learned that Enos Colburn was my great-great grandfather Louis’s nephew. Enos grew up with seven brothers and sisters. The family was huge. A few more searches and I discovered there are still over 100 Colburn relatives living in and around Green Bay. I called my dad to give him the news. He was quiet, which is his nature. Then he said. “My God, I’m seventy-eight years old and didn’t know any of this.”

We speculated why his immediate family had been cut off from the Colburns. He said that when his dad, Bud, was born, my great-great grandma Pheilomen snatched him up and brought him to Saint Joseph’s Catholic Church to be baptized. “You see, Norma, my grandmother, was protestant,” he said. “She didn’t want my dad baptized Catholic. This caused quite a problem in the family.”

After that the two women never got along. It makes sense that Norma circled the wagons around her small family leaving her husband’s people behind. I don’t think my Uncle Marty knew much of this, and though I’m happy I was able to share it with my dad, I feel it came too late.

While the sorrow of my uncle’s passing catches in my chest as I water the garden or cook a meal, a flock of Brown-headed Cowbirds have settled in the orchard, scaring off all the other birds. Cowbirds are parasitic. A mama cowbird either eats or kills an egg or two in perhaps a sparrow or a dove nest, then she lays her eggs leaving them to be incubated then raised by the unsuspecting mama bird. But there is another way to look at this. Cowbirds are like the character, Philip Nolan, in Everett Hale’s short story, “The Man without a Country.” In the story, Nolan, a US Army lieutenant, renounces the United States and is sentenced to live the rest of his life in exile aboard US Navy warships. In some cosmic way, God, Mother Nature, or whomever you may pray to, exiled the cowbirds to a life without a nest to call their own. Without a home, Nolan lived the rest of his life with deep melancholy for what he had lost. The cowbirds have found a way to survive as outsiders looking in. I understand these sentiments all too well.

Most of my family is still in Wisconsin, cold country dotted by forests and farmland where lakes freeze in the winter, and rivers cut their craggy paths into the earth like veins. As a kid I complained about the weather and swore one day I would move someplace warm. In my late twenties, I followed through with my threats and moved to Arizona, to the Sonoran Desert with its thirsty earth and vegetation armed with stickers and thorns, blistering sun, and rattlesnakes coiled in the parched grass ready to strike. There is beauty and danger in both places. I was born into one extreme only to seek out the other.

The days are getting shorter and as I reflect on family and my role in it, I feel so very far away from home. My body has never forgotten the change in seasons, the explosion of red, orange, and red wine leaves lighting up trees this time of year, the cool nights, the hunger for stew and mashed potatoes. I miss Wisconsin to my core and yet I belong here, too. Going home means leaving the desert, a place that has settled in my bones alongside the dark, cold winters of my childhood. I would long for the mountains, the sunsets, the open spaces if I left. Marty’s phone calls kept me tethered to another life and to possibilities. I miss him. Right now I feel like a woman without a country, a cowbird without a nest.

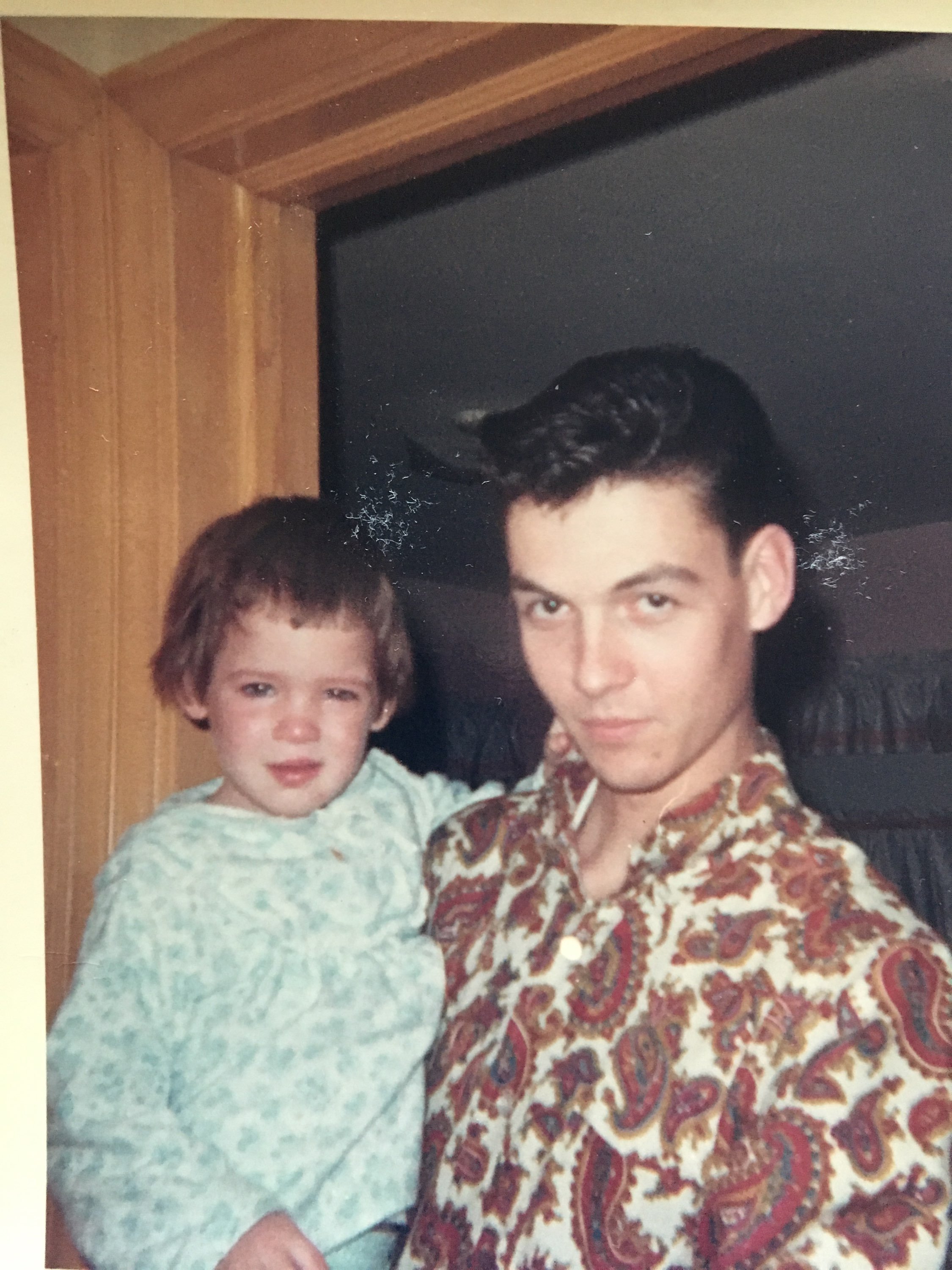

Photo #1- My Uncle Marty and me

Photo #2- My fifth great-grandfather, Jean Francois d’Amours de Courberon

Photo # 3- My cousin, Chad